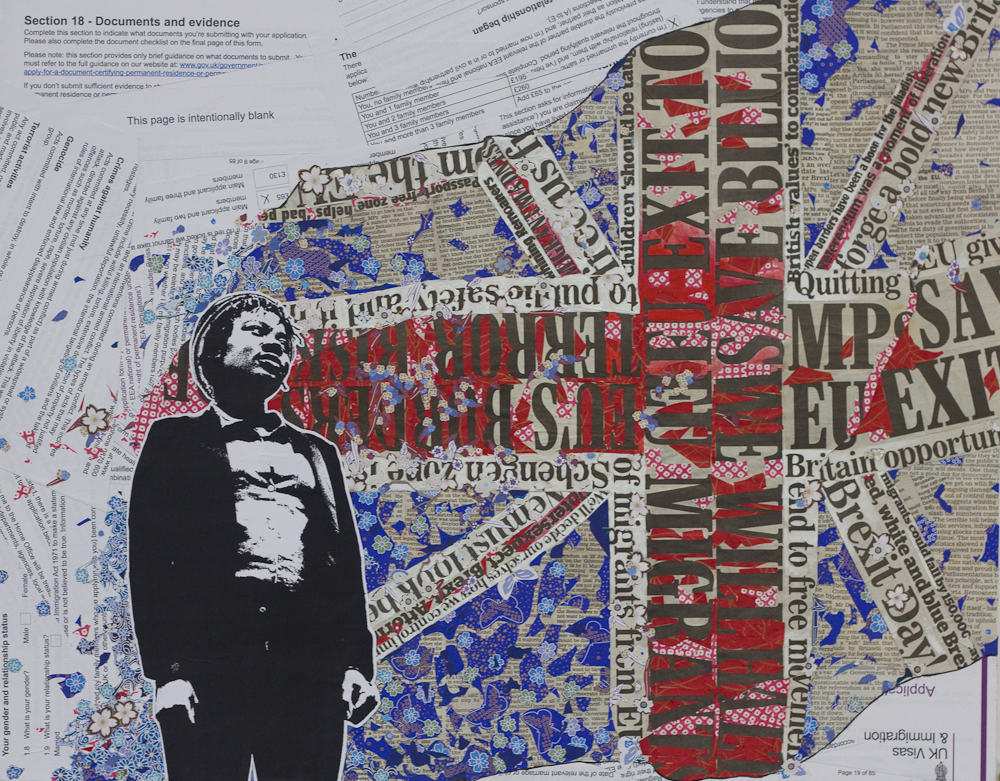

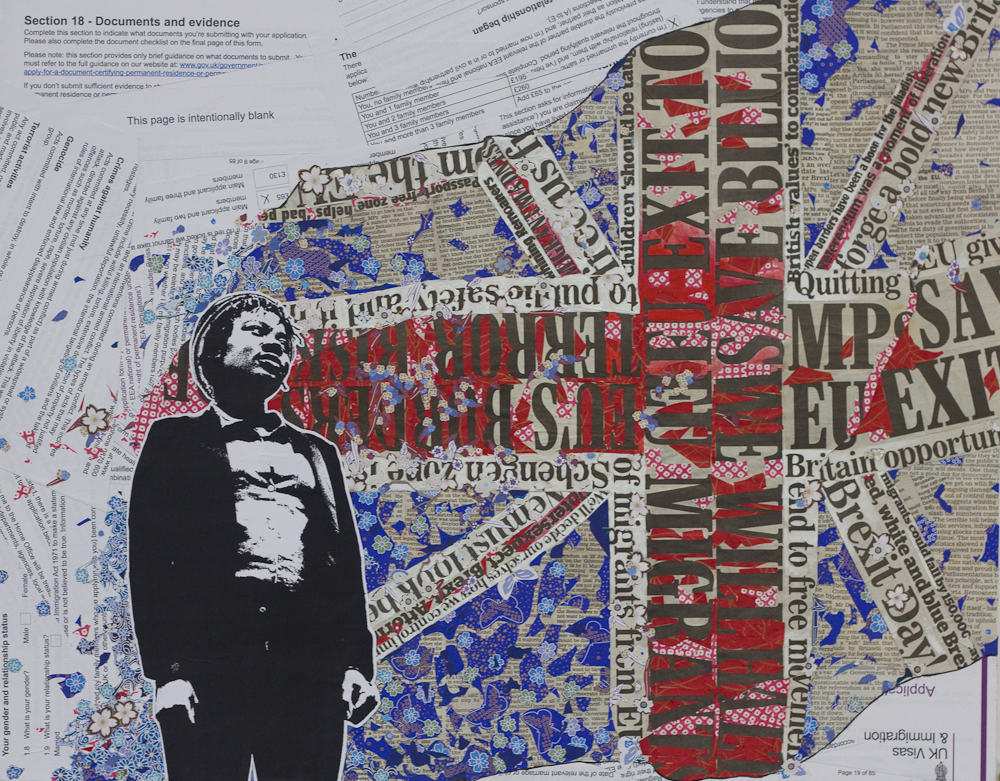

Life post-Brexit for EU-citizens living in the UK is the focus of Brexit Stories, a mixed media collage series by the Zadissa sisters.

The decision for the UK to leave the EU is one that not only transforms the socio-political structures of the country but also consequently affects people’s self-image and understanding of their identity. We use mixed media collage to document how EU nationals feel they are affected by Brexit, their views on their future in the UK and their strategies in response to the referendum. We want to highlight how identities are negotiated and constructed.

Brexit has created a situation where many white (western) Europeans feel stigmatised in the same way people of colour and black people do in their everyday lives. With this project, we wish to highlight some of the mechanisms which racialise bodies. Moreover, we want to create a broader understanding of the stigmatisation many people face because of their race, ethnicity, religion and origins. This project is a contribution to portraying a turbulent time in the history of the UK and Europe.

A big thank you to our lovely supporters!

Click on the names to read each story and see the collage:

Aude, Burcu, Daniel, Kasia, Michel, Moniek and Renate.

Aude

I fell in love with London in 2010 and decided to move to a country, where I could be myself, in all my complexities. London was the only place where I felt like I could fit. I felt like my blackness was accepted and so did my queerness. People were kind and open. I didn’t have to hide some parts of who I was. London loves young people and I thought I would get a chance. Then I moved to Scotland, and I was all of a sudden privileged as an EU-national. I hate to speak up for the EU because it’s a neoliberal and anti-refugee project, but I also have to admit that it has given me an undeniable privilege. It made it possible for me to come here and try to escape from the oppression I was facing in France as a black working-class woman. In the UK, I was all of a sudden considered French. Something I never felt in France even though I was born there. This acceptance of who I chose to identify as, made me eager to want to be a part of it. I did everything I could to be integrated. To belong to this idea of diversity which I thought existed under the British flag. I tried so hard to get rid of my French accent. To learn the British cultural markers to become British. And then Brexit shattered everything. It has given me anxiety attacks. It’s affected my mental health. I worked so hard to be a part of this country. In my enthusiasm to integrate, I only hang out with locals and my British friends don’t understand why I am so frightened. My family in France wonders when I’ll move back.

In my mind, I hope that Scotland would become independent, and for London to remain a bastion of diversity and a sanctuary city. But I know that Scotland probably won’t be allowed to become independent and London will become a tax haven where gentrification will get worse than it is now. I know that xenophobia will rise higher. What I feel now is anger. Anger for believing that the UK would be better than this, for being disappointed that I got fooled. It wasn’t better than this after all. Now I see beyond the English flag all the lies. And I try to accept that the country has shown me what it truly is. On the day of Brexit, I was filled with hopelessness, sadness and despair, a car passed by on the street waving the flag, cheering for Brexit and the break-up from the EU. And I was having a panic attack. I wanted to scream, but I couldn’t. Brexit for me is a vote of a specific community, the white English one. Those who, regardless of their gender, class, living places – either in cities or rural areas, feel that their identity is being threatened by a diversity I am no longer sure if it ever existed. The motivation of “taking back our country” is fuelled by the idea that England can and will rule the world, becoming an empire again. They really think Brexit is going to give the UK that opportunity as if it is a magical mirror where everyone sees what they want in. “We will stop free movement and have access to the single market. We don’t need all these foreigners, we can make it on our own. Of course, we can.” Good luck with that.

href=”https://qti.home.blog/queer-qandi-fest-20-23-june/#top”>Take me back to the top!

Burcu

Nine years ago my husband and I left the Netherlands where Wilder was getting stronger. We escaped the rise of the far-right and moved here, to live in a country with softer values. But the same thing is now happening here, especially after the Brexit referendum. I worry about whether I can get a new job if I have to start looking for one. We have just recently bought a house and that is yet another thing to worry about. What will happen with our mortgage? What if the interest goes up and we are out of job and can’t keep the house? But our biggest concern is our daughter’s future. She is a Dutch national like both of us. For her to get British passport we need to follow a long procedure. But once she is 18 years old, she has to make a decision since double nationality is not allowed in the Netherlands. If they decide that the residency permit isn’t enough for us to stay here, to have access to health care, education and so on, then we really have to reconsider. I gave up my Turkish citizenship for a Dutch citizenship and could do it again if a British one would make things easier. For me it isn’t a big issue, I don’t have any emotional attachment. But my husband doesn’t want to give up his Dutch passport, which might make things more difficult. Then again, these are things that many people from Asia or Africa face daily in this country: giving up their citizenship, application forms, visa refusal and so on. They face discrimination every day, but as EU-citizens we don’t have to deal with these issues. When I think about refugees coming here with no home to ever go back to and little hope of staying here while we’re complaining about the rights of EU-nationals, I really feel bad. So compared to Europeans living here, I’d say I don’t feel as worried about Brexit. Sure, the morning after the referendum, I woke up early and started to cry when I heard the news. Even though I knew this was going to be the result. I got sad especially for the future of my child.

At her school, they had a Christmas play. Half of the kids weren’t even Christians, but they were all in the play. I don’t consider myself a racist but I find myself asking my daughter about her friends, the kind of name they have, where their parents are from… but to her, they are no different from any others. She doesn’t see them any different because of their skin colour or religion. And this, this is the kind of future we should be building but look at the world, look at France, look at the Netherlands. Is such a future even possible? Will Brexit allow it? Ten years from now with Brexit, the start of a nationalist movement, will we see that kind of future in the UK?

Daniel

I have lived here for 11 years, me and my husband have a house here, we met here as a couple, our friends are here, this is where we live. Britain has a multicultural society which I enjoy. But now I feel less at home in England than ever before. There are more cases that foreigners are being singled out which makes you reflect on your own identity. Driving around in my left-hand-drive car in Cambridge, an accepting, well-off bubble of a city, is fine. But then for dog-walks, I drive outside the city and that is where I come across placards, and signs, that are advertising UKIP’s xenophobic agenda. This car takes me out of a safe-zone into an environment where I become acutely self-conscious of the stigma that foreigners can carry around. So the car symbolises the sense of being out of place. Ironically, I have been driving right-hand cars for many years but got this left-hand drive recently as a present from my brother. Now after all these years, I am considering getting a UK citizenship in order to stop being decided upon and to have a political voice of my own in this country.

On the night of the referendum, I turned off my phone because I did not want to get any messages promising the UK would remain in the EU as long as the final results had yet not been announced. In the morning, when I found out about the Brexit outcome, I simply felt empty. Then I felt exasperated. I have been feeling frustrated for a number of reasons: for the appalling level of debate preceding the referendum; for the low quality of the information that was offered to people; for the Leave campaign dramatising the reasons to vote Leave; for putting the responsibility for making such a decision in the hands of people who were not well-informed; and for blanket statements that the EU is undemocratic without most people knowing that it is arguably more democratic than Britain regarding voting system, fundamental rights and ensures labour and environmental standards.

In Germany, I grew up with a strong sentiment against nationalism. The concept of nationality should not entail shame, but it should bring an awareness about what it means to work for unity, to build and sustain inter-cultural relations not only between different nations but also within a nation. What we see today is a movement in the opposite direction, towards increasing divisions. I know that many communities in the UK have been targeted by racism after Brexit. The racism, I believe has always been there, but Brexit, the Leave campaign, the arguments against migration and scapegoating immigrants, seemingly legitimises that racist statements are expressed and acted upon. Many countries, take the Netherlands or France for instance, are heading that way as well. The European Project is in danger of failing and so it is time for a self-assessment in order to progress and create more openness. This is my hope.

Michel

Shortly before the referendum, I became a homeowner. Having no family ties in England, it was with mixed feelings that I decided to sign up for a mortgage and commit to this being my home for at least several years to come. After the referendum result, I have been thinking a lot about my future here, and if this new England-for-the-English can really feel like home in the longer term. But I do find comfort in knowing that the city I call home overwhelmingly voted against these divisive politics. So Cambridge does feel like home, even if England itself does not at this moment.

Anyone lacking that long blood-line linking them to the UK will eventually be affected by this process of putting people in ranks by what their blood-line dictates. Then again this is not unique for Britain, as the rise in xenophobic parties across Europe has shown, and given not even hundred years have passed since World War II, I can’t help feeling that Europe has a very short memory of where this kind of thinking leads to when taken to its extreme. But the fact that it is so strong in a country that prides itself on stopping the Nazis, is disheartening.

I am deeply saddened by reports of rising hate-crimes towards immigrants. I also know that Polish people have often been the targets. Even if I have never actually lived in Poland and though my Polish vocabulary is quite crude, just being of Polish origin makes it impossible not to identify with the victims of the assaults in the UK on a more personal level.

I’ve never felt any strong sense of belonging to any nation, seeing myself primarily as a citizen of the world – or as Theresa May would have it, a “citizen of nowhere”. It is important to be a good citizen in your local town, but our commitments should not end there, nor should they end at the national border. As a Swedish citizen I thought I would be welcomed to stay and work here. I think I would have been inclined to call myself English before Brexit. Now with the growing sense of nationalism here I feel I do not wish to belong to such an identity group.

But I will certainly give more thought to obtaining a British citizenship alongside my Swedish one, as it may make it less likely for my rights in this country to be compromised, but also give me the right to vote if there are more crucial decisions that can be voted on. Yet this feels like the wrong reason. I always imagined that I would obtain a British citizenship because I would feel connected to this country, whereas now it’s more about not being used as a bargaining chip by Theresa May and her government.

Moniek

For me, this bike is almost a symbol of the person I was when I was living in Amsterdam. I have always loved cycling on it in Cambridge. Perhaps some car drivers didn’t like me on the road, but in general, I felt that people were positive about this “Dutch lady on her bike”. The day after the referendum it felt different. All of a sudden I was very much aware of not being English. There was an angry driver behind me acting as if finally there was no need to be ashamed of disliking foreigners because he felt supported by the majority of the population.

Clearly, it is not true that 52% of the population is happy about a hard Brexit. But I think it is true that 52% of the people who voted were unhappy about how things are and they voted for change. It seems that far too many people have been neglected by the government. This referendum was a way for people to vote against, to show their discontent with a government which has not done anything for them in a very long time. It would be great if the government focused more on that.

I have lived here for 12 years. 12 years of happily being like everyone else but after the referendum for the first time I felt like an unwanted foreigner and experienced a little bit of what it must be like for people who are facing serious racism all over the world every day. If it really gets too complicated to stay here, I and my family will consider moving back to Holland. The uncertainty about whether we can stay or not makes our house in England feel less like our home.

Kasia

My first reaction to the referendum was anger. I have done my PhD here. I have contributed to the progress of science here, I have paid taxes here. I have done more for the UK than for my own home country. But all that I have done seems to be of little. But in a way I understand. This is how democracy works. I have of course no hopes for a reversal of the Brexit because Brexit is what the government wanted, isn’t it? Otherwise it’s odd to think that there would be a government who would set up a referendum about such an important issue without having any plans at all for how to deal with the outcome of it. But I don’t think they will throw people out because the country will simply collapse.

For example where I work, in the academia, it’s an environment with many people from all around the world. We feel welcome and needed but there are concerns about funding science and scholarships after Brexit. Personally I think if the fees for studies go up you will see a bigger collection of applicants with more money and not necessarily with higher qualification. So at the same time there are talks about movements and petitions which I don’t like. Talks about making it possible for the UK to have access to the funds and scholarships in the EU. Why would they go pick the good parts of EU if they have decided to leave? Those funds are for member states and should go to studies in EU-countries.

I came here to study on a scholarship and at the same time, I worked in a pub. I have lived poorly. And I have also lived well. I feel I am equipped to find solutions. You simply learn to adapt. This is why I don’t feel affected by Brexit. But that is because I am free from commitments such as children. That’s why it isn’t difficult for me to take whatever little I have and leave to start a new life somewhere else because living a hard life doesn’t scare me.

Renate

I am in shock but not surprised because I’d seen it coming. Indicators were there all along, in the responses at work and in public, in the media. Two nights before the referendum I was watching the news and could not help but to cry because I could see it happening. I could not understand why the Remain campaign did not put bigger effort into offering facts. But I guess this is the effect of something that has been going on for 40 years. Reversing it would mean that they had to admit that it has been the government’s doing which has brought the country to its knees not the membership in the EU. And I don’t think even the Remain campaign had the will to acknowledge that.

Reading the papers, listening to the radio, watching the news, I find that some people are taking advantage of what has been unleashed and expressing the sort of anger which is not always justified but often misled and manipulated. These are people who are not willing to find out why they feel this rage. The media keeps encouraging this mindset of values, this anger. Brexit has led me to apply for residency permit, not citizenship because I need to keep my German citizenship in case the Herd Mentality takes hold here and I need to go back where I am no longer the “Other”. Then again, given what is going on in Germany at the moment, it is not much of a console. Brexit has also made me look at things in England differently. I see more of the exploitation that is going on here. I think this is a feeling Brexit has brought on as it has made me more aware of my “Otherness” which has in turn sharpened my senses, my sense of observation, noticing things I would have not done as much before.

I hope that on a European level, there will be a new consensus, strategies to stop the EU from falling apart, a common ground where people feel more involved and engaged in the policy-making and I wish to end this on a note of Hope not Fear.